Higher education is one of many tools available to those who wish to sculpt an uncertain future into a defined plan. With the wide range of institutional choices, increasingly specialized program options, and regional preferences, students have more factors to consider than ever before. While housing options have shown mixed impact on student application and attendance decisions, residence halls do have a demonstrable effect on students’ social, emotional, physical, and educational outcomes. Along with many architects across the nation, R3A was intrigued by the conversation surrounding the University of California Santa Barbara’s proposed Munger Hall residential project.

The eponymous billionaire-amateur-architect Charles Munger donated $200 million to the project — a little over one-eighth of its $1.5B budget — with the stipulation that he get to design the structure without input from UCSB.

While this unconventional arrangement could stir up controversy on its own, the central sticking point of Munger’s design is its dearth of natural light: 94% of student bedrooms would lack traditional windows. In the October 5th Design Review Committee report, Munger Hall is described as a “transformational prototype for student housing” which will encourage “the development of close-knit, supportive student communities.”

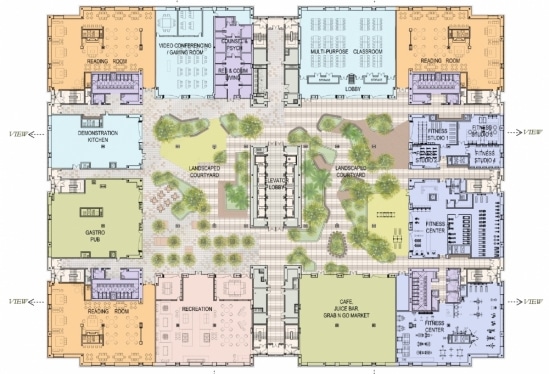

The 11-story, 1.68 million-square-foot dormitory is organized into a “house system” of eight suites with eight single-occupancy bedrooms and two bathrooms per suite. arrangement is described as creating “a community within a community.” The massive structure also features public amenities, emphasizing the strong focus on communal living and continuous social exposure. Executive Vice Chancellor Gene Lucas anticipates that “students will spend most of their daylight hours in these common areas rather than in sleeping areas” when not in class, etc.

On its face, this decision seems inhumane. So inhumane, in fact, that 15-year veteran of UC Santa Barbara’s design review committee Dennis McFadden resigned due to the project’s advancement. McFadden cited the lack of windows as his central objection. Munger defended his design in an interview with CNN Business, clarifying that the single-occupancy rooms are not truly windowless — they feature an “artificial window” which “delivers the exact spectrum of daylight.”

These artificial windows are not new products. Munger’s artificial windows are similar to “happy lights,” lamps that mimic the sun’s light spectrum and can assist with mental health issues (SAD, etc.) resulting from reduced daylight in winter months. The issue with relying on the “proxy” solution of artificial windows, says sleep researcher James Wyatt of Rush University Medical Center, is that college students are the most vulnerable population for circadian rhythm disruption. Circadian rhythms are the body’s natural cycles of sleep and wake, and they are demonstrably affected by patterns of light exposure. Wyatt went on to call the design “reckless,” echoing McFadden’s sentiment that Munger Hall is a “social and psychological experiment with unknown impact on the lives” of students.

Munger’s justification for this lack of windows was a focus on density, saying “It’s a game of trade-offs. if you maximize daylight, you get fewer people in the building.

Munger’s statement is accurate from the standpoint that a higher ratio of exterior wall-to-floor square footage equals a higher cost-per-square-foot for building. Due to the cost premium of perimeter envelope systems, the geometry of squares and cubes minimize the cost per-square of new construction. This means that lessening the perimeter contributes to higher volume at lower cost.

Despite his lack of formal education, this is not Munger’s first dormitory design. Munger Graduate Residence Hall at the University of Michigan features a similar windowless design, not even incorporating artificial windows. Students interviewed by CNN Business about their experiences in MGRH relay bleak tales of week-long, sun-less COVID quarantines; others say it’s “no big deal.”

To offset the potential negative effects of the bedrooms, the university has taken steps to provide positive outlets for emotional and psychological health. Assistant Director of Graduate Academic Initiatives, Lindsay Stefanski, describes events held within the dorm — such as rooftop yoga — citing “phenomenal” student feedback as inciting positive change for the residential community. These interventions are no doubt having a positive impact on students, but the question now stands: could a different spatial design assuage the need for these interventions altogether? Can a building whose goal is for students to “constantly interact with each other in common areas” also care for its students private lives without sacrificing that collaborative ethos?

The project’s density has been another central pain point of the discussion. With a reported 4,536 beds, Munger Hall would be both the “largest academic dormitory in the US” and the “eighth densest neighborhood on the planet.” Research exploring density’s effect on human psychology has shown that density has no definitive positive or negative effect on humans, but it tends to amplify extant conditions: the negative becomes more negative, and the positive becomes more positive. If students enter the dorm with negative emotional, physical, or social behaviors, those may become amplified in the dormitory’s ecosystem. While the same is true for positive behaviors, could this truly be an equal trade-off? We hold the opinion that dormitories should strive to thread the needle between providing stimulating, collaborative environments and calming, personal environments that promote reflection, decompression and focus.

Density and personal space have a distinct relationship. Personal space is a subjective and culturally defined distance perceived as “belonging” to an individual. This space ebbs and flows in different contexts — open spaces, public transit, activity spaces, etc. Topics pertinent to the study of personal space include bodily autonomy and perceived control. In a 1978 paper, Cohen and Sherrod discussed the importance of perceived control as it relates to human psychology in socially dense spaces. They theorized that the close presence of others can interfere or restrict the success of individual goals. The presence of strangers further complicate this dynamic, introducing unpredictability into the mix. In this way, density limits perceived control over an environment and create irritation or anxiety. R3A Associate Principal Chris Gruendl observes that students “are far more likely than their parents or grandparents to have grown up in households where each child has their own bedroom and/or personal space, and this environment may be a shock to the system that triggers negative social behaviors.

As evidenced by the closet-sized bedrooms, Munger Hall conceptualizes personal space only as it pertains to sleep and private study. While these artificial windows are an improvement on Munger’s previous design at Michigan, the human need for connection with nature is as much psychological as it is biochemical. For a space to truly bring a strong internal connection with nature, the interior environment must be multi-sensory and should at least consider factors such as access to natural views, light’s entry and play within a building, dynamic contrast of light and shadow, fresh air-flow, acoustic ambiance, etc. Many of these concepts are obvious in portions of the design, but their implementation lacks consideration for students’ private lives.

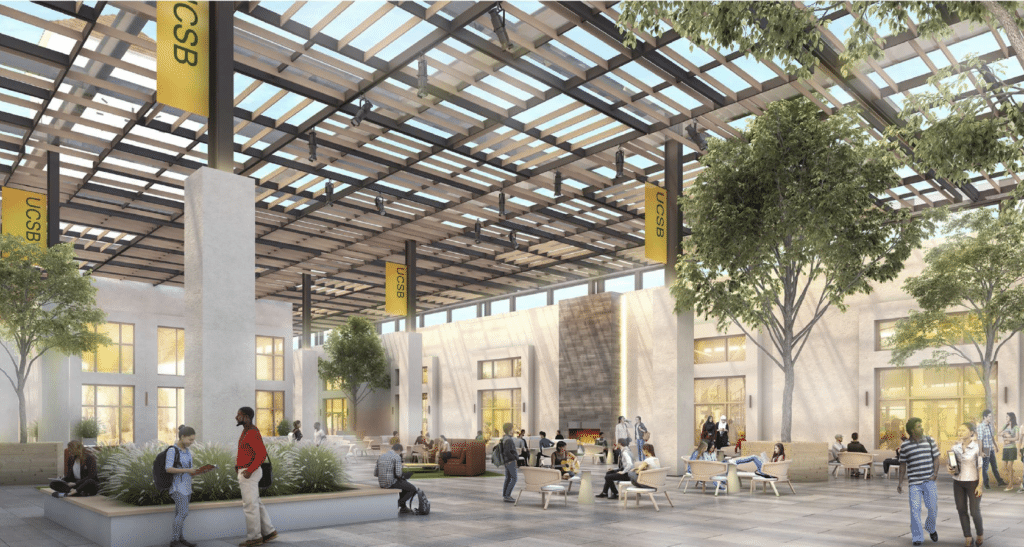

The most nature-accessible area, the 11th floor’s “one-acre naturally ventilated landscaped courtyard with seating areas, social pods, and other features,” is a large, open-air penthouse.

The past two years’ events have transformed the way we work and live. Ventilation systems, sanitization practices, and the ability for people to isolate or distance have become hot-button issues. On first glance at the project, many of our first reactions were to the tune of the hall’s being a “potential powder keg” during a pandemic (or even a particularly aggressive seasonal flu). In a Q+A with the UCSB, Executive Vice Chancellor Lucas describes the building’s ventilation system as providing fresh air at “twice the volume required by the California Building and Mechanical Codes. To balance air pressures, the fresh air is mechanically exhausted to the roof from the suites, galleries, kitchens and Great Rooms, resulting in no recirculated air.” Lucas also confirmed that Munger Hall is “fully compliant with, and generally exceeds, the requirements of [ADA and FHA, as well as CBC Chapters 11A and 11B).

In sharp contrast with many universities in the United States, UCSB has almost no incentive to create primarily indoor, enclosed spaces. The temperate climate of Santa Barbara, paired with its gorgeous views, make it a prime site for integration between the artificial and natural worlds. Many reactions to Munger’s design note its “un-Californian” aesthetic. McFadden highlighted UCSB’s proximity to the beach and Pacific cliffs as “integral” to the school’s culture and identity. R3A Associate Principal Jozef Petrak, who completed his undergraduate study in California, echoed this sentiment, that “aside from the Tuscan flavor of the facade, there is nothing Southern California about this building. [Southern Californian buildings] are typically far more porous” and allow for more “outdoor interstitial spaces for circulation, meeting, and socializing.”

The Munger Hall project raises intriguing questions about spatial trade-offs; the relationship between best practices and user-targeted design choices; and the balancing act of securing funding and appeasing those who have the means to bankroll architectural interventions. As universities like UCSB continue to grow to meet student demand, the appeal of dense residential programs will no doubt increase in-step. The issue is complex — how can universities balance a curated, sensitive student experience with the practical concerns of where to house, feed, and circulate students in their care? Munger Hall’s “trade-offs” resolve the density issue with an extreme solution that may be rife with unintended consequences. As construction continues on the project and students ultimately move in, no doubt the “experimental” design will be intriguing to follow.