Halkin Mason Photography

By Patricia Washburn

Originally Published 9/19/2023 on tradelineinc.com

Hemmed in on its urban campus and in need of additional research space, the University of Pittsburgh formed a public-private partnership to repurpose a disused Ford Motor factory into biomedical lab space called The Assembly, preserving historic features while implementing cutting-edge energy conservation measures. The partnership, which took three years to solidify, enabled the university to pursue such a collaborative and transformative project. Reaching beyond the confines of the campus, the team identified the long-vacant Ford plant, first opened in 1915 to produce Model Ts.

Collections of Henry Ford

The Pittsburgh master planning process drew out the need for the facility, says Matthew Rendulic, director of real estate development for the university. “Our focus has shifted to multipurpose, multitenant, interdisciplinary facilities that seek synergy and efficiency across the board,” he says. “In the case of The Assembly, the ability to renew aging facilities is the ultimate goal of meeting that sustainability and efficiency goal.”

The need for space was obvious. “Pre-pandemic, our vacancy rates for space were less than 1 percent,” says Rendulic. “We did not have the luxury of vacant greenfield sites next to our campus. Adaptive reuse presents many challenges but also represented our greatest opportunity.”

Innovation District

That density is part of being in what Rendulic describes as a “naturally occurring innovation district.” Pitt is nestled in the urban Oakland neighborhood, which also includes Carnegie Mellon University and many tech companies.

“The location in the city is ideally placed near the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center, a really significant partner to the other tenants that were coming into the building,” says Deanna Keil, principal at ZGF Architects and a lead designer on the project (with R3A as local associate).

The neighborhood emerged as a strength in the master planning process. “All of Pitt’s 16 programs are within a 10-minute walk,” says Rendulic. “That relationship enables close ties between not just the teaching and the research, but that clinical side of things, as well.”

“Repurposing buildings is in our DNA,” he says. “This was a long-vacant building—almost too good to be true. The naturally occurring synergies were pretty obvious.”

Some aspects of the former auto plant were well suited to lab space: adequate floor-to-floor height; adherence to all of the vibration criteria; a flexible floor plate; and a completely open floor plan, with roughly ideal structural modules that allow for plug-and-play research programming.

“And then this project was made financially viable through its utilization of historic tax credits,” adds Rendulic.

Historic Preservation

The challenge of repurposing this historic building was energizing, says Keil. The team worked with U.S. National Park Service, the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office, and historical resources to trace the building’s history and collect drawings and artifacts from it. “Original documentation of the building was hard to come by, and understanding the existing structure was a big undertaking,” she says.

“In addition to the architectural requirements for preserving the structure and materials, we tried to celebrate some of the more significant spaces,” she says. A six-story vertical crane shed became a public atrium that is the showplace of the new building and a central location for researchers to encounter their colleagues. An open, retail tenant space preserves the original tile floor of the auto showroom where people once bought Model Ts. The result: a complex with 523,000 gsf of space, 477,000 sf available for tenants.

“The atrium became a wayfinding place, where one can connect with fellow researchers. The users also wanted to engage with the community,” says Keil.

“You really can’t mandate innovation,” says Rendulic. “It’s an evolution, it’s an ecosystem. This facility is self-contained, but it allows us to create a more connected, outward-looking university perspective. It allows synergy and efficiency among research groups and partners in a highly amenitized space, creating opportunities for their minds to connect. The atrium allows people room to decompress.”

Large images from the Model T era are part of the décor in the building’s elevators and open spaces. “There are little moments throughout,” says Keil. “We have artifacts that are going to be showcased throughout the facility to tell the story of the building and the industry. The clients and users of the building really wanted us to embrace that industrial nature.”

Part of the historic preservation requirement involved making sure the interior of the building was visible to the neighborhood. “It limited what programs we were able to push up against the windows, so that drove our lab planning neighborhood scheme,” says Keil. “But it afforded us an opportunity to think uniquely about where to integrate those modern materials. Along the windows are all open workstations, whereas the heavy intensive lab spaces that don’t necessarily have to comply with historic preservation requirements, are all inboard.”

Keil adds that preliminary analysis indicates re-using the existing structure has resulted in a more than 50 percent reduction in structural embodied carbon and a more than 4 percent reduction in overall building embodied carbon cradle-to-grave. This factors in transportation, operational energy, and emissions from refrigerants that are a large portion of the embodied carbon footprint.

Project Challenges

ZGF

Because of the dearth of information about the original building’s composition, the team had to begin with significant work on testing its soil, stability, and infrastructure, to be sure it could be modified for the planned labs. The work also required extensive ground penetrating radar scans and building scans, and the team had to avoid disrupting a main sewer line for the city that runs underneath the crane shed.

“The existing structure appears to be concrete, but a lot of it is actually steel covered in concrete—not surprisingly, for Pittsburgh, the Steel City,” says Keil. “We did extensive material testing to understand the quality of the exposed existing materials to make sure that they are safe for the building inhabitants and the environment.”

During the design and construction phases, the designers were involved heavily with their subcontractors, holding weekly building information modeling sessions for close structural and systems coordination.

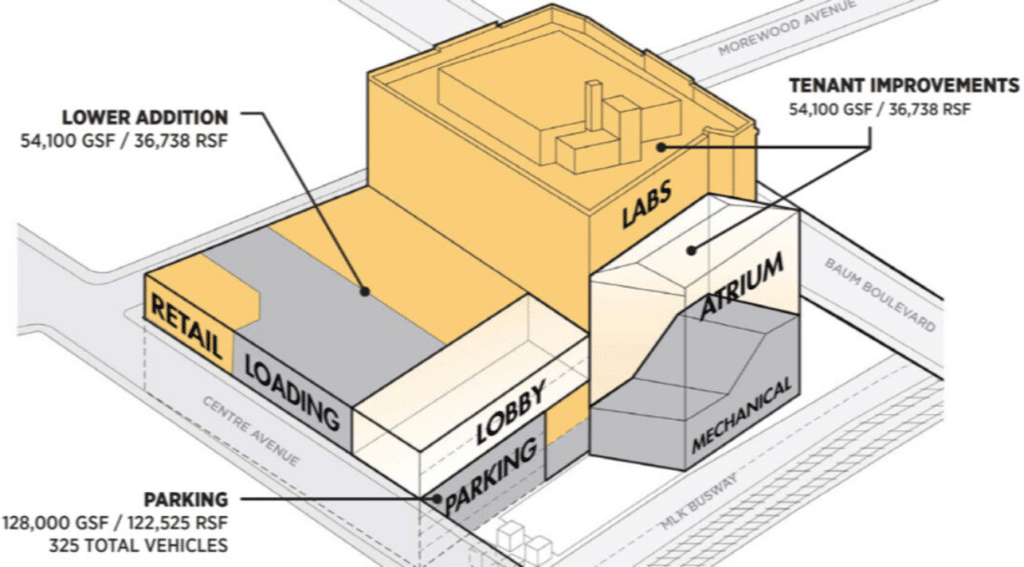

To add space for mechanical systems and other modern requirements, the team got permission to put a modular prefabricated penthouse on top of the existing Ford plant, making sure the new labs could meet today’s standards without violating the historic preservation constraints on the old building. They also demolished an oddly shaped addition to add a larger platform of new construction, with five levels of parking underground and retail and loading space above.

The team also had to plan for the level of flexibility today’s research requires. Current use of The Assembly’s labs runs about 50-50 between wet and dry spaces. Furniture is modular, and lab benches are not fixed, so that many spaces can be adapted to the ways a team actually works. For instance, one team uses a casual collaboration space to have Turkish tea in the afternoons.

Ownership Model

The collaboration needed to fund and implement the project required some innovation on the business end as well. The university purchased the site from UPMC in an arm’s-length transaction, then teamed up with development partner Wexford Science & Technology to ground lease it.

The remodeled facility was then divided into three units in a condominium structure. The university solely owns and operates the parking garage—325 vehicle spaces, plus electric vehicle charging stations and room for more than 100 bicycles. Pitt then leases back the historic building and the two floors of space on top of the garage from Wexford. Finally, the third unit sits atop the garage and the addition, and is leased by Wexford to private tenants including at least one Fortune 5 company.

Construction was not cheap—about $1,000 per square foot, which is a blended rate across the whole project. The Pitt space is divided between the university’s School of Medicine and the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center, providing natural synergies between research teams and allowing for efficiencies by sharing core labs and amenities.

Recruiting Tool

Connie Zhou

One of the foundational goals of the space was to be a place that would help attract and retain top researchers and other staff members. “We designed the space for flexibility,” says Keil. “It’s been a very useful recruiting tool to lure quality researchers because the character of the space is unique.”

“When you talk about labs, anyone can work in the nice, traditional, new-build, efficient lab plate,” says Rendulic. All of the amenities that we crammed into this building are the differentiator. Already, a year after opening, this building is delivering tangible results for our researchers.”